Async Programming in .NET: Part 1

13 Jun 2018 10 minute read editI’ve been using the async and await keywords at work on both our .NET core API and Xamarin projects, but I started to feel guilty as I didn’t fully understand how asynchronous code works in the .NET framework. This post is mostly to help me put into my own words what async programming really is (and why I now think it’s awesome).

This is a post in a two, maybe three part async series. This first post is to provide the outline – an introduction – which should nicely lead into the next post, where it will provide more context and actual C# code samples.

CPU and I/O bound code

Before we begin talking about what async is, let’s first understand the difference between CPU and I/O bound code. This is important as it will give us a better understanding on the problems asynchronous code solves

CPU Bound

A thread of execution is bound to the CPU if its performance is correlated with the CPU. Anything that can run faster by throwing at it a better processor is CPU-bound, which includes LINQ-over-objects, big iterations, mathematical calculations and computational inner loops.

IO Bound

A thread of execution is bound to the I/O if its performance is correlated with a subsystem or peripheral. I/O bound includes tasks such as writing to your HDD, waiting for a response from the network or querying a database. These operations cannot be speed up by faster local processing, as performance is tied by subsystems hardware and performance. The HDDs’ write speed will dictate how long something takes to be written. The 3rd party server response time will determine how quickly you can process a request.

As web developers, it’s far more likely that our operations are I/O bound rather than CPU bound. For CPU work, we can optimize our operations by letting them run in parallel by leveraging Parallel.ForEach or using async and await and starting the thread via Task.Run. For further concurrency and parallelism, you should also look at the Task parallel Library. When we start a thread (using one of the methods above), the thread is grabbed from the thread pool (a collection of threads that can be used to perform background tasks) which then performs that action, and returned once complete. The number of threads in a thread pool is not fixed. The thread pool will assess and dynamically manage the number of threads to try and complete the task as quickly as possible. It’s not surprising that by throwing better hardware at CPU bound problems you can improve performance of the operation.

For I/O bound tasks, ideally we would be able to also upgrade our machines and get an obvious improvement in performance. However, if we perform an I/O operation such as making a call to a third party API (something that we do not have control over), we cannot make that operation complete faster. A £100 or £10,000 machine will likely perform the operation at similar speeds (certainly you won’t see a x100 performance gain). Furthermore, if we tried to use the Task Parallel Library to solve an I/O bound operation, you will be disappointed (I’ve actually made this very mistake in one of my projects!).

Synchronous vs Asynchronous

Let’s assume we have a server running ASP.NET and our clients request is I/O bound, therefore its dependent on an external resource such as a database or an API.

Synchronous

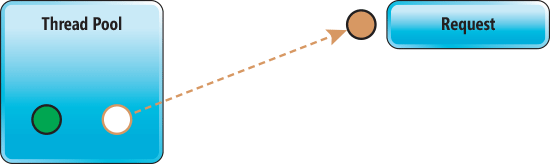

A request comes in, our server takes a thread from the thread pool and assigns it to that request. As this code was written synchronously, it means as soon as we make our request for data or the call to the API, the thread will now wait until the response comes back.

Image from: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/dn802603.aspx

The thread is blocked and it cannot be released back to the thread pool. What is the thread doing exactly? Nothing. It is just waiting for the I/O operation to complete. Looking at the diagram above, in this particular case, this is not a problem, as our server has two threads in the thread pool. If we have a second request, we again, have enough threads to handle this and therefore our clients won’t notice anything. But what about this scenario:

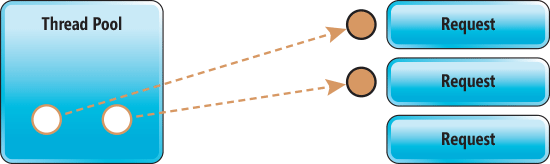

Image from: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/dn802603.aspx

The extra request now means we have more requests than threads. This is a problem, and it means the third request will have to wait for an available thread before it can start processing. The request is in the system, and therefore an internal timer begins and if unmet, an HTTP service unavailable response is returned, a 503.

To address this, you may suggest to increase the size of the thread pool. This approach can help, but you will still run into problems. Firstly, a thread requires a certain amount of memory and therefore you can only spin up a limited number of threads. I don’t have any figures, but in general, for a large scale application it’s not realistic to have enough memory to spin up a thread per request. Secondly, adding more threads does not make your system more scalable. I mentioned earlier that the thread pool can dynamically add more threads. The problem is that the thread pool has a limited injection rate, meaning it can only create “one thread every two seconds”. If you experience a spike in traffic, the thread pool will not meet the demand.

Fortunately for us, there is a much more scalable solution, which doesn’t require a million threads in the thread pool to handle a million simultaneous requests!

Asynchronous

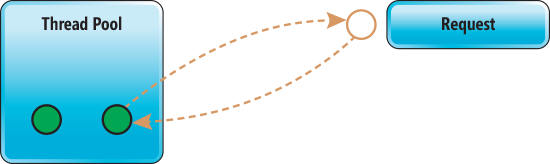

An async request operates differently. When a request comes in, like our synchronous code, a thread is assigned to that request. This time, however, as soon as we call the external resource so our thread becomes I/O bound, our asynchronous code will return the thread to the thread pool.

Image from: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/dn802603.aspx

The asynchronous I/O bound operation is still in progress,but since the thread returned to the pool, the thread can now be used to handle a new request. Once the I/O bound operation completes, a thread from the thread pool is reassigned, and completes the operation.

This means that a synchronous handler will use the same thread for the duration of the request, whereas an async handler may have multiple threads to complete the request.

Now if we revisit our original problem, this time, if we get a third request, the server is much more likely to cope as any I/O bound thread will be returned to the thread pool and handle the new request. In essence, async enables a much smaller number of threads to handle a larger number of requests, thus making our application more scalable. In essence, async code gives us more scalability!

Now, you may wonder if we are returning the thread to the thread pool, there must be something, another thread, that is blocking on the I/O operation to listen for the response. The short answer is no. Without going into great detail, when we await an async task (how we instruct the runtime that this is an async operation), the Task (the ‘thing’ that will get done) is returned as an incomplete task. Having a task in an incomplete state is what enables the thread to return to the thread pool. The thread pool will eventually get notified that the task has completed via the libraries completion port. Once notified, it will then respond by assigning a thread to complete the request. For a more concrete example, read ‘What About the Thread Doing the Asynchronous Work?.

In the next post (part 2) I will discuss in more detail how we async a task in C#, along with good practice guidelines and things to look out for!

Also, for the record, this article was heavily influenced by Stephen Cleary’s post. You should go and read it!